For all of the genres and subgenres that rock ’n’ roll gave rise to, distortion is one element that links them all the way back to the beginning. Just listen to the fuzzy tones on Ike Turner’s “Rocket 88” and Goree Carter’s “Rock Awhile,” which are widely recognized as the first rock songs ever recorded. Distortion introduced a whole new attitude to musical expression that attracted rebels and free spirits and free thinkers while disturbing the sensibilities of those who preferred an easy listening experience.

Like penicillin, distortion was discovered by accident. Players forced to use faulty, damaged, or cheap, poorly made amplifiers liked what happened when they plugged in and cranked up the volume. Before long, players were trying to get the sound on purpose by intentionally damaging their equipment—Link Wray is famous for having punched holes in his amp’s speaker with a pencil he found lying around the studio.

WHAT IS DISTORTION, ANYWAY?

First, let’s talk about harmonics. When you play a note on your guitar, the sound you hear is made up of a fundamental frequency—the pure note—along with multiples of that frequency, which are called harmonics. If you feed your instrument’s signal into any device that changes the signal’s harmonic content in a certain fashion, you get the sound that we call distortion. There are numerous ways to change the harmonic content of your signal, but for our purposes we only need to look at three of them. Each changes harmonic content by generating additional frequencies.

The first and most basic way to generate harmonic content is to push your instrument’s signal, which is the voltage generated by your guitar’s pickups, beyond an amp or pedal’s headroom.

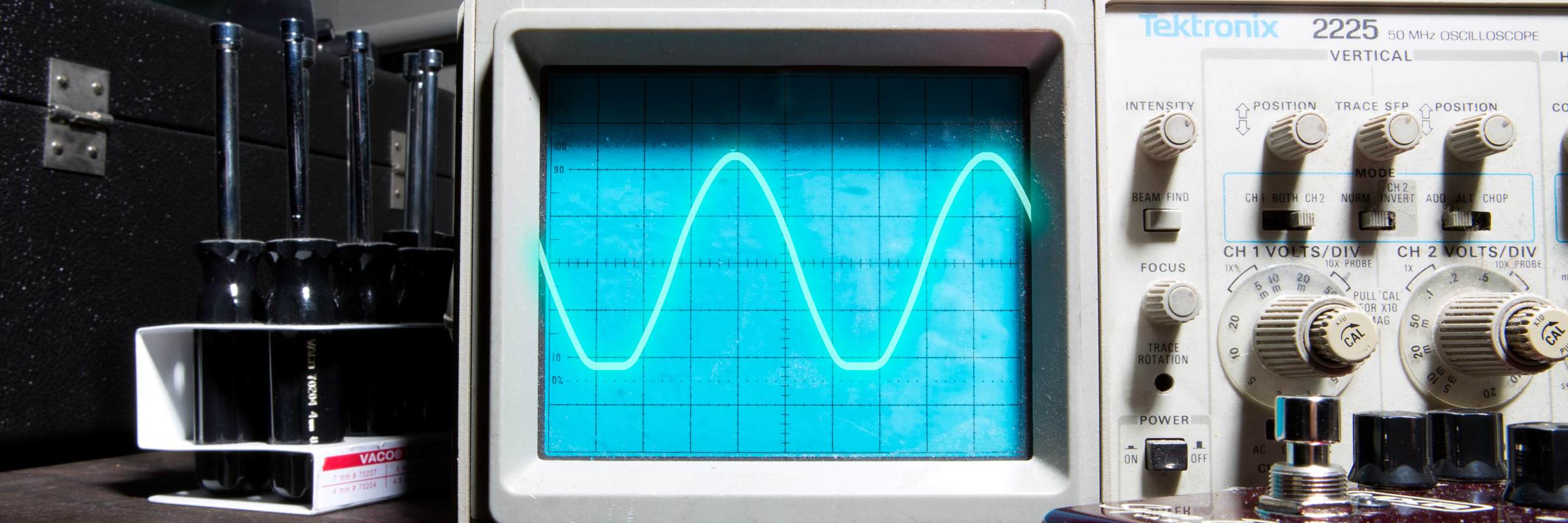

As a sound wave, your instrument signal sits between two boundaries called rails. Headroom is the space between the rails. If you crank your amp so that your signal’s peaks push against the rails, those peaks start to get clipped off of your signal. This is how tube amp distortion is created.

Pedal distortion is usually achieved by the other two methods: using the circuit to clip your signal before it runs out of headroom or using transistors, which generate extra harmonics because of their nature as imperfect amplifiers.

Each of these methods creates distortion, an umbrella that covers overdrive, distortion and fuzz. The difference is a matter of degree—how much are you clipping your signal?

OVERDRIVE

Overdrive is the sound you get when you crank a tube amp to that rich, gritty sweet spot. This clips your signal some, but not too much. Overdrive pedals are designed to both emulate and complement the sound of an overdriven tube amplifier.

For example—running an OD pedal through a clean amp will provide smooth, mellow grit while running it through a slightly overdriven tube amp will stack the gain from both and produce a very thick and saturated sound that’s closer to distortion but still retains the tubey warmth of your amp.

Overdrive pedals typically use a two-step process. First, hi-fidelity amplifiers called op-amps are used to boost to your signal. At a certain point, diodes are triggered to soft-clip the boosted signal, generating harmonic content. The type of diode used can have a dramatic effect on the pedal’s tone—LED—which has a wide open, transparent sound—and silicon—which is more biting with a bit of compression—are the most common.

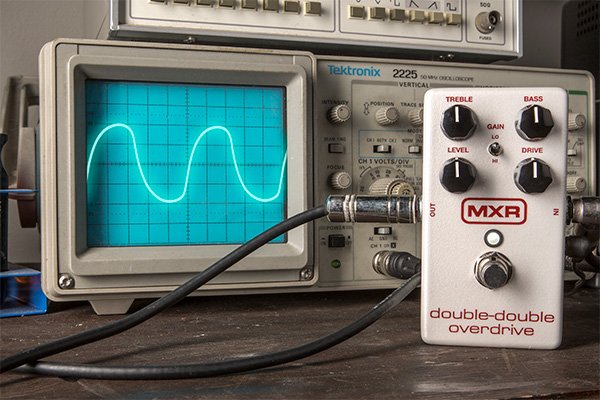

The MXR® Double-Double™ Overdrive is the perfect example of an overdrive circuit—and it’s got Lo and Hi Gain modes for extra versatility. Let’s see how the signal for each looks on the oscilloscope.

The Lo Gain signal has fairly round peaks, which indicates fairly soft clipping and a smoother sounding overdrive.

With a bump in gain, the peaks get sharper, and the overdrive has a more aggressive sound. Notice, however, that the peaks are still intact. We haven’t completely slammed our signal against the rails—yet.

DISTORTION

Distortion is the technical term for all the different sounds you get from clipping a signal, but in common parlance it refers to the middle ground—a signal that’s clipped harder than overdrive, and is therefore much more aggressive, while retaining more articulation than fuzz.

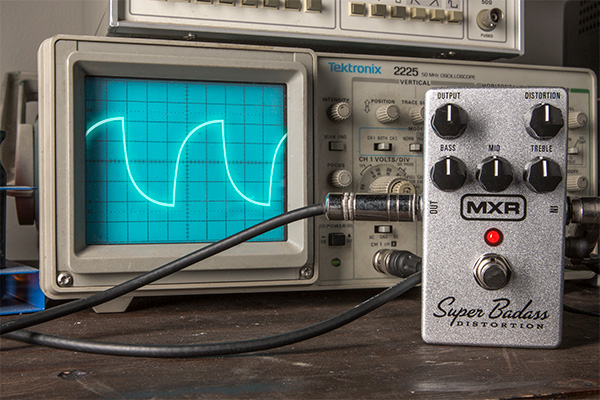

Distortion pedals produce much more gain than most overdrive pedals, so players generally use them with a clean amp. As with overdrive pedals, distortion pedals tend to use op-amps and diodes to clip your signal. The MXR Super Badass® Distortion is one such pedal.

Notice that the peaks are just starting to get shaved off. But we’re still not smashing into the rails yet—we’ve got one more type of dirt to cover.

FUZZ

Fuzz was the first type of distortion to appear in pedal form, originally designed to sound like your amp was faulty or your speaker was damaged. Amp settings don’t matter much at this point—your signal is getting totally clipped.

Unlike overdrive and distortion pedals, fuzz pedals use transistors to instead of op-amps to add gain to your signal. Where op-amps are hi-fi, transistors are by nature very lo-fi—they add a ton of harmonic content to your signal as soon as they start to amplify it. The type of transistor a fuzz circuit uses can drastically affect fuzz tone. Generally speaking, germanium transistors produce a warmer and smoother fuzz while silicon transistors produce a brighter, more aggressive fuzz.

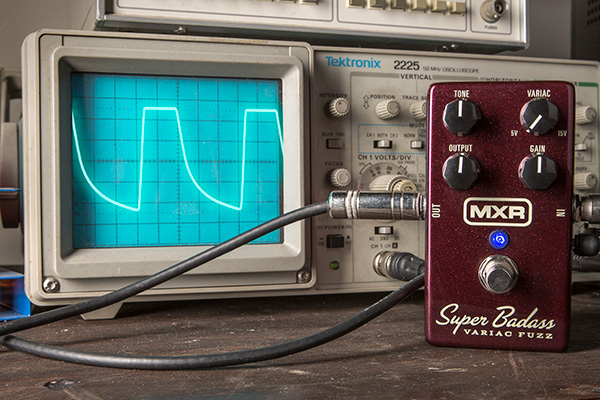

The MXR Super Badass Variac Fuzz uses silicon transistors, so it has a nice cutting tone. What makes this pedal unique among other Dunlop fuzzes, though, is its Variac control, which allows you to adjust the amount of voltage—and therefore headroom—available.

You can adjust the Variac control from 5v to 15v. This image shows what the signal looks like at the 5v setting. As you can see, the peaks are totally clipped off. There isn’t a lot of room to move around before your signal smacks into the rails, creating a gnarly, splatty sound.

Increasing the voltage to the default ±9v smooths out the edges a bit, but the peaks are still flattened up against the rails. At this level, the Super Badass Variac Fuzz sounds like a chainsaw in a lightning storm.

At 15v, this pedal has a lot more headroom than most fuzzes. This produces a super smooth and transparent signal that’s more akin to overdrive, but it’s more like a transistor’s interpretation of what the op-amp + diode combination produces in a pedal such as the Double Double Overdrive.

At 15v, this pedal has a lot more headroom than most fuzzes. This produces a super smooth and transparent signal that’s more akin to overdrive, but it’s more like a transistor’s interpretation of what the op-amp + diode combination produces in a pedal such as the Double Double Overdrive.

The harmonic content generated by transistors removes the need for a diode to clip the signal but that doesn’t mean you can’t combine transistors with diodes for a whole ’nother level of super hard-clipped saturation. The Way Huge® Russian-Pickle™ Fuzz, for example, combines silicon transistors with silicon diode clipping to create a thick and groovy sound with a pronounced midrange.

THE WRAP

The science of distortion can seem pretty esoteric, but in simple terms we can see that the differences between overdrive, distortion and fuzz have to do with how hard you clip your signal. Depending on the shade of distortion you’re looking for, you’ll find amps and pedals using various methods to throw your signal into dirt mode.