Playing live is not the same as playing in the studio or in the practice space, where you have much more control over all the various factors that can effect the way you sound. When you play a gig, you’re at the mercy of the venue’s acoustics and sound tech.

Here’s a list of pedals that allow you to retain as much control over your sound as possible when playing live.

Equalizer

When playing out, one of the first issues you’re going to have to deal with is adapting your tone to various physical spaces or unfamiliar backline equipment. Your most basic line of defense in these situations is an EQ pedal, which allows you to fine-tune your sound by cutting or boosting specific frequencies.

MXR® has two great options: the Six Band EQ and the Ten Band EQ. Modern classics, both have been upgraded with noise-reduction circuitry, true bypass switching, brighter LEDs for increased visibility, and a lightweight aluminum housing.

The Six Band covers all the essential guitar frequencies, from 100Hz to 3.kHz, and each can be boosted or cut by 18dB. If you’re in a mind to save space, this is the EQ for you, as it comes in at the same size as the Phase 90.

The Ten Band EQ gives you control over a wider range of frequencies, from 31.25Hz to 16kHz, which you can cut or boost by 12dB. This extended range makes it perfect for bass players as well as guitar players. For further fine-tuning, you can also cut or boost your signal at both the input and output stages. Finally, there’s a second output so you can run two separate signal chains.

Having either EQ on your board allows you to tune your guitar or bass rig to any venue in short order. Just remember to tune with your ears, not your eyes.

If you want a simpler, less transparent and more “sauced up” tone-shaper, the Micro Amp+ is another great option to consider for both guitar players and bass players. It builds on the classic Micro Amp circuit with EQ controls, low-noise op amps, and true bypass switching. This is a pretty versatile pedal—it can be used as a boost, if you have enough headroom; an OD, if your headroom is lower; and as a line driver/ buffer.

Compressor

Some players consider compression to just be a studio thing—unless you’re using a more “effect” style pedal such as the Dyna Comp® Compressor—but compression can also serve you well on stage. It helps even out your signal, ensuring that nothing gets too loud or too soft by limiting the dynamic range.

The MXR® Studio Compressor and Bass Compressor are perfect for this application. Their Attack, Release, Ratio, Input, and Output controls make it easy to dial in the desired threshold, from subtle peak limiting to hard squashed compression. Use the ten gain-reduction status LEDs to check reaction speed in real time. Equipped with CHT™ Constant Headroom Technology, these compressors also provide a ton of headroom for clear and transparent performance.

Buffer

When you run your signal from your instrument to your amp though long cables and/or through a large array of effects with varying impedance, players often experience line level or treble loss. A buffer such as the MXR® CAE MC406 addresses this problem quite nicely.

It comes in a small, rugged housing and can add up to +6dB of gain to your signal with its front-facing slider, making up for signal loss that can occur when combining effects with different impedance levels. Hi and Lo cut switches help you to fine-tune signal recovery. The CAE Buffer also comes with a convenient 9VDC power output jack, for powering another pedal, along with an extra output for a tuner, separate effects chain or amp. On the inside, you can set whether to receive a buffered or unbuffered signal.

The CAE Buffer can be placed before, after, and sometimes in the middle of the effects chains to help drive things along.

Direct Input Box

This one’s a no-brainer for bass players. Chances are, the venue’s sound tech will want to run your signal to the FOH. If you don’t have your own DI box, you’ll have to use theirs, leaving your tone in their hands. Having a DI box such as the MXR® Bass DI+ or the Bass Preamp allows you to go direct while retaining control over your own sound.

The Bass Preamp features separate Input and Output level controls and a 3-band EQ section with sweepable midrange—from 250hz to 1khz—for extensive tonal flexibility. It’s all delivered super clean with high headroom thanks to our own Constant Headroom Technology™, and you can use the Pre/Post EQ switch to set whether or not your Direct Out signal is affected by the Bass Preamp’s EQ section. And of course, the Bass Preamp features a Ground Lift switch in case you encounter ground loop hum.

The Bass DI+ combines a three-band EQ with a switchable distortion channel, including a noise gate, a Phantom/Ground switch, an unaffected parallel output for a tuner or separate signal chain, and of course an XLR direct out.

Volume Pedal

Putting a volume pedal on your board allows you to change your output level quickly and without having to stop playing. It also allows you choose where in your signal chain to adjust volume—relying on only on your instrument’s volume control for output dynamics can result in a weaker signal being fed to your pedalboard.

The Volume (X)™ Mini Pedal is a great pedalboard-friendly option—it’s durable and solidly built with a lightweight aluminum chassis, aggressive non-slip tread, and our patented Low Friction Band-Drive for a smooth range of motion and consistent, reliable performance. For maximum comfort and precision, the DVP4’s rocker tension is fully adjustable. This pedal can also be used for expression purposes, but that’s an entirely different function.

Two common placements for volume pedals are pre-gain, before distortion pedals, and post-gain, after distortion pedals. A volume pedal placed pre-gain is used much like a volume knob on a guitar. When the volume pedal is placed post-gain, a lot of players prefer to use it to adjust the overall volume of your signal without effecting the gain structure of any overdrive, distortion, or fuzz pedal in your chain.

A/B Box

An A/B box allows you to route your instrument’s signal to two separate output paths. With the MXR® A/B Box, you can switch between amps or run them both at the same time with different effect configurations, which opens you up to a whole range of tonal options. You can also use this pedal to create separate chains within your main signal chain.

Noise Gate

A noise gate automatically mutes your signal below a certain output threshold. This comes in handy if you’ve got any noise—often caused by super high gain pedal or amp settings or a venue’s faulty wiring—interfering with your signal. Dial in the right setting, and your signal will be totally silent until you start playing. Noise gates are usually placed at the end of the signal chain or after any gain pedals in an FX loop.

The MXR® Smart Gate® Noise Gate is equipped with three selectable types of noise reduction, covering just about every noisy signal situation you’re likely to face.

It bites down on sizzle and hum but lets the smallest detail of your playing through, sensing precisely when and how fast to engage without getting in your way. It lets you can wring every last bit of sustain out of chords without being cut off, reacting gradually to long, sustained notes and quickly to short, syncopated notes while preserving picking dynamics and harmonic overtones.

Power Supply

Maybe this one is too obvious, but hey—it’s good to be thorough. Why worry about a bunch of batteries when you can power all of your pedals with a single source?

The MXR® Iso-Brick™ Power Supply is just such a source, and a very convenient one at that: its compact and lightweight, making it vert pedalboard-friendly, with 10 fully isolated outputs that accommodate a variety of voltage and current requirements: two 9V outputs at 100mA, two 9V outputs at 300mA, two 9V outputs at 450mA, two 18V outputs at 250mA, and two variable outputs adjustable from 6V to 15V at 250mA. The two variable outputs can be used to emulate voltage “sag,” a drained battery effect sought by many vintage tonechasers. The Iso-Brick Power Supply also features power on/off and connection status LEDs so that you can quickly troubleshoot any pedal or connection issues.

For a simpler power solution, the DC Brick™ Power Supply is also a great choice. With eight 9V outputs and two 18V outputs, it will power just about any analog pedal, and each 9v output has a red LED that illuminates if there is a short.

Obviously, if you used all these pedals at once, you could take up an entire world-tour sized pedalboard. You still need room for your Fuzz Face® Distortions, Carbon Copy® Delays, and Cry Baby® Wahs, so use this list to address your particular needs as a gigging musician. Which of these pedals might make your life easier when you step onto the stage?

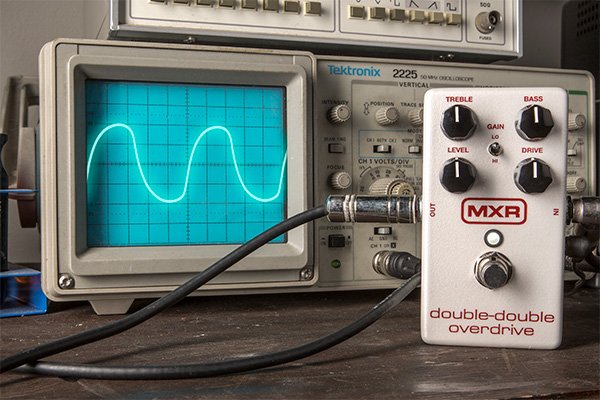

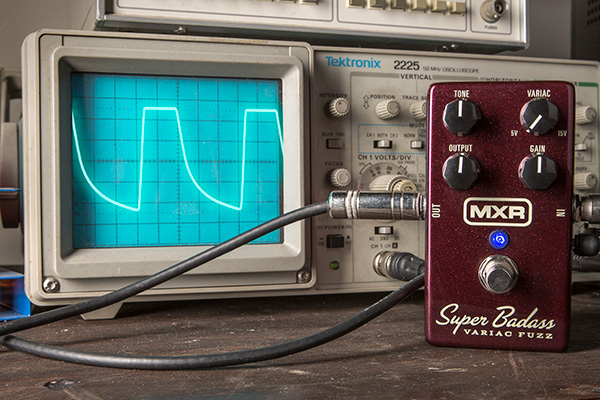

At 15v, this pedal has a lot more headroom than most fuzzes. This produces a super smooth and transparent signal that’s more akin to overdrive, but it’s more like a transistor’s interpretation of what the op-amp + diode combination produces in a pedal such as the Double Double Overdrive.

At 15v, this pedal has a lot more headroom than most fuzzes. This produces a super smooth and transparent signal that’s more akin to overdrive, but it’s more like a transistor’s interpretation of what the op-amp + diode combination produces in a pedal such as the Double Double Overdrive.